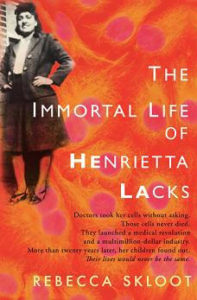

This month, we’re reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the story of a Black woman who unknowingly had an enormous and enduring impact on science and the future of medicine. As we celebrate the impact and history of Black Americans during Black History Month, this is one story that needs to be told.

This month, we’re reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the story of a Black woman who unknowingly had an enormous and enduring impact on science and the future of medicine. As we celebrate the impact and history of Black Americans during Black History Month, this is one story that needs to be told.

We’re also huge fans of this book because it raises important questions about bioethics and patients’ rights, and it is chock full of good science writing. Author Rebecca Skloot illuminates important research and scientific processes while arguing for more ethical practices to benefit all patients.

Lacks was born in 1920 in Virginia, eventually moving to Maryland with her husband, David. After the birth of her fifth child, she visited Johns Hopkins, one of the few hospitals to treat Black women at the time, because she could feel a “knot” in her womb. There, she was diagnosed with cervical cancer.

As part of the course of her diagnosis and treatment, doctors removed Lacks’ cells—and began using them for research without her knowledge or consent. They were sent to the lab of Dr. George Gey, but unlike the many other samples he received, Lacks’ cells didn’t die. Instead, they reproduced. From these cells, Gey propagated a durable and prolific line of cells—the first immortal human cell line—and named it HeLa after Henrietta Lacks.

This cell line has been shared freely by Johns Hopkins and has contributed to many medical breakthroughs, from the development of vaccines to the study of leukemia, the AIDS virus, and cancers.

But as Lacks’ cells continued to provide the foundation for major scientific and medical breakthroughs, her legacy was clouded with exploitation. Her family did not grant permission—nor received compensation—for the use of the cells by researchers and drug developers, but the scientific community continued to rely on HeLa cells in countless use cases.

Now her family is involved in her legacy and helping to change the narrative. As her granddaughter, Jeri Lacks-Whye told Nature magazine, “I want scientists to acknowledge that HeLa cells came from an African American woman who was flesh and blood, who had a family, and who had a story.”

Join us as we dive into this story by reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. We can’t wait to hear what you think